Centralization of Pain

What is the centralization of pain?

The difference between protective or acute pain and pathological or chronic pain can be defined by centralization. This concept is critical to understanding intractable pain conditions and deserves a thorough explanation. Gaining insight to the actual mechanism that is responsible for the lingering sense of hurting can explain the purpose of certain medications, therapies and procedures performed by pain physicians.

Sometimes degenerative diseases (like herniated discs or arthritis) or prolonged healing from an injury (like surgery or a fracture) leads to the prolonged signaling of pain. Your nervous system is continually reminded over and over again that something is wrong. Repetition, as everyone knows, is the key to learning. It’s like your central nervous system is constantly being displayed flashcards. Over time, just like when you are trying to memorize vocabulary words from another language, the recall becomes quicker and more vivid. The underlying physical condition may not necessarily worsen, but the pain intensity grows because the nervous system reorganizes itself. The body, essentially, learns how to feel pain.

Components of pain

To begin to understand the process of centralization, we have to deconstruct the fundamental elements of the nervous system. This consists of the nerve, spinal cord and brain. Centralization describes the heightened sensitivity and abnormal processing of pain that starts with derangements in the nerve, then propagates to changes in the spinal cord and last alters the brain.

Let’s start with the peripheral nerve. Pain starts with the stimulation of specialized nerves called C- and A-delta fibers. These nerve endings have been termed nociceptors. The latin term noci means “I will harm.” Nociceptors have specialized nerve endings designed to detect harm to the body through heat, pressure and chemical signals. Nociception typically requires a strong stimulus, that starts the signalling of harm.

Nerves gone wild

One of the early changes that underlies chronic pain centralization is that when the C- and A-delta fibers are exposed to a lesser stimulus, they send nociceptive signals with greater intensity. In addition, more nociceptive fibers sprout and grow in a specific area of pain so there is a higher density or population of nerve fibers in a chronically injured tissue.

To paint a metaphorical picture, nociceptors may be thought of as oven sensor that is set to alarm when the temperature reaches a certain point, let’s say 350 degrees. In chronic pain, the sensor becomes faulty and is reprogrammed to alarm at 300 degrees instead. On top of that, the volume of the alarm rings much louder. To make matters worse, several more loud, annoying, sensitive alarms are attached to the oven and they begin to ring simultaneously.

What is the centralization of pain?

The difference between protective or acute pain and pathological or chronic pain can be defined by centralization. This concept is critical to understanding intractable pain conditions and deserves a thorough explanation. Gaining insight to the actual mechanism that is responsible for the lingering sense of hurting can explain the purpose of certain medications, therapies and procedures performed by pain physicians.

Sometimes degenerative diseases (like herniated discs or arthritis) or prolonged healing from an injury (like surgery or a fracture) leads to the prolonged signaling of pain. Your nervous system is continually reminded over and over again that something is wrong. Repetition, as everyone knows, is the key to learning. It’s like your central nervous system is constantly being displayed flashcards. Over time, just like when you are trying to memorize vocabulary words from another language, the recall becomes quicker and more vivid. The underlying physical condition may not necessarily worsen, but the pain intensity grows because the nervous system reorganizes itself. The body, essentially, learns how to feel pain.

Components of pain

To begin to understand the process of centralization, we have to deconstruct the fundamental elements of the nervous system. This consists of the nerve, spinal cord and brain. Centralization describes the heightened sensitivity and abnormal processing of pain that starts with derangements in the nerve, then propagates to changes in the spinal cord and last alters the brain.

Let’s start with the peripheral nerve. Pain starts with the stimulation of specialized nerves called C- and A-delta fibers. These nerve endings have been termed nociceptors. The latin term noci means “I will harm.” Nociceptors have specialized nerve endings designed to detect harm to the body through heat, pressure and chemical signals. Nociception typically requires a strong stimulus, that starts the signalling of harm.

Nerves gone wild

One of the early changes that underlies chronic pain centralization is that when the C- and A-delta fibers are exposed to a lesser stimulus, they send nociceptive signals with greater intensity. In addition, more nociceptive fibers sprout and grow in a specific area of pain so there is a higher density or population of nerve fibers in a chronically injured tissue.

To paint a metaphorical picture, nociceptors may be thought of as oven sensor that is set to alarm when the temperature reaches a certain point, let’s say 350 degrees. In chronic pain, the sensor becomes faulty and is reprogrammed to alarm at 300 degrees instead. On top of that, the volume of the alarm rings much louder. To make matters worse, several more loud, annoying, sensitive alarms are attached to the oven and they begin to ring simultaneously.

From periphery to the spine

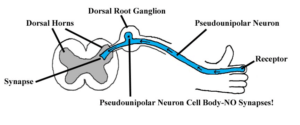

The story of chronic pain does not end here. Heightened sensitivity in the peripheral nerves next alters the spinal cord. Peripheral nerves connect or synapse to a cell body called the dorsal root ganglion. At this connection, the nerve input is filtered and analyzed to determine if the pain signal intensity is worthy to travel further up the spinal cord and into the brain. The Gate Control theory of pain explains that there exists a network of specialized nerves that blocks or filters nociceptive signals. This theory states that inhibitory pathways start in the brain and travel down through the spinal cord to the dorsal root ganglion in an attempt to block all pain signals below a certain frequency and amplitude. If a C- or A-delta fibers send a signal weaker than the descending inhibitory signals, the gate may be closed and no pain is sensed.

Chronic pain states create a scenario where the pain gates are abnormally opened and normal nociceptive input that would typically be blocked is now free to travel and make life miserable. It is as if Gandalf the wizard in Lord of the Rings was replaced by a hobbit when trying to hold back Balrog the demon. A faulty gate lacks the power to declare, “You shall not pass” and cannot keep the pain from crossing the bridge.

Over time, the frequent and intense pain signaling flooding the gates at the dorsal root ganglion, causes the pain pathways in the spinal cord to become more streamlined so pain signals travel with greater ease. Eventually the changes spread upstream to the dorsal columns, which is the section of the spinal cord that carries pain signals.

http://www.med.umich.edu/lrc/coursepages/m1/anatomy2010

In some cases, even more curious developments ensue. At the spinal cord, automatic discharges are discovered. Pain signaling does not start at the tissue level where the pain is felt, but along the spinal tracts. Its just as crazy as if you felt someone punching you in the back, but no one is around. You did not imagine this, because you are in severe pain, the pain is real, but there is nothing wrong with your back. You would not know the difference. What has happened is the central pain pathways have developed a mind of its own.

The problem that started in the peripheral tissue or body part that lead to frequent nociceptive firing has now morphed into a more centralized reorganization of the nervous system. Moving from the peripheral nerve, to the first order neuron in the dorsal root ganglion and along the path of the spinal cord. It sensitizes the second order neurons which are located a little higher in the spinal cord. Up, up, up and wrong, wrong, wrong the wiring is both stronger and less regulated in the spinal cord and then it reaches the brain stem. This is the automatic part brain that filters information to the central motherboard. In the brain stem, the connections multiply and reach a vast number of targets in the neocortex, which is the thinking part of the brain.

The brain in pain

Centralization continues in the brain. Milliseconds before pain manifests into consciousness, the brain receives nociceptive signals and then processes this information simultaneously in various regions involved in sensory location, memory, emotions, reasoning, and movement, which is just to name a few functions. One’s mood, previous experiences, thoughts, and situations organize the pain processing network in the brain. For example, a hockey player who blocks a slap shot in an unprotected arm when the game is on the line will continue play like nothing happened. At the end of the game, when her team loses, she notices the whopping bruise and feels her arm as sore and throbbing. What distinguishes these two scenarios? The attention is diverted to the high intensity game that sends signals to close the gate at the dorsal root ganglion. The nociceptive signals that do emerge to the brain are automatically ignored while the mind focuses attention on a more important task.

The constant flood of amplified and sometimes unprovoked pain signals causes a complete reorganization of the brain pain network. This further intensifies the sense of hurting and may lead to certain beliefs that certain safe movements like standing or walking may lead to harm. This then encourages inactivity which leads to muscular deconditioning, which results in increased soreness and then more inactivity and pain. This vicious cycle is a result of changes in the brain’s hardwiring.

It is important to note the fact that while some of these changes may take place in the nervous system, they are not permanent. The goals of treating chronic pain involves various strategies aimed at reprogramming the pain processing systems back to normal and preventing the further centralization of pain. A multidisciplinary approach that combines physical and behavioural approaches along with medications and procedures attempts to promote normal nervous system functioning.

At DVPSI, we perform many procedures to help prevent the centralization of pain. The procedures we offer, such as epidural, facet or joint injections are performed to quiet the onslaught of continual nociceptive signaling. Spinal Cord stimulation works to close the pain gates. Antidepressant and antiseizure medications we commonly prescribe are aimed at decreasing the activities of the hypersensitive nerves and spinal cord.

Chronic pain is real and severe and should never be simplified and treated superficially. It is our belief that motivated, empowered and educated patients have the best chance of halting the process of centralization and living the richest life possible.

Recent Comments